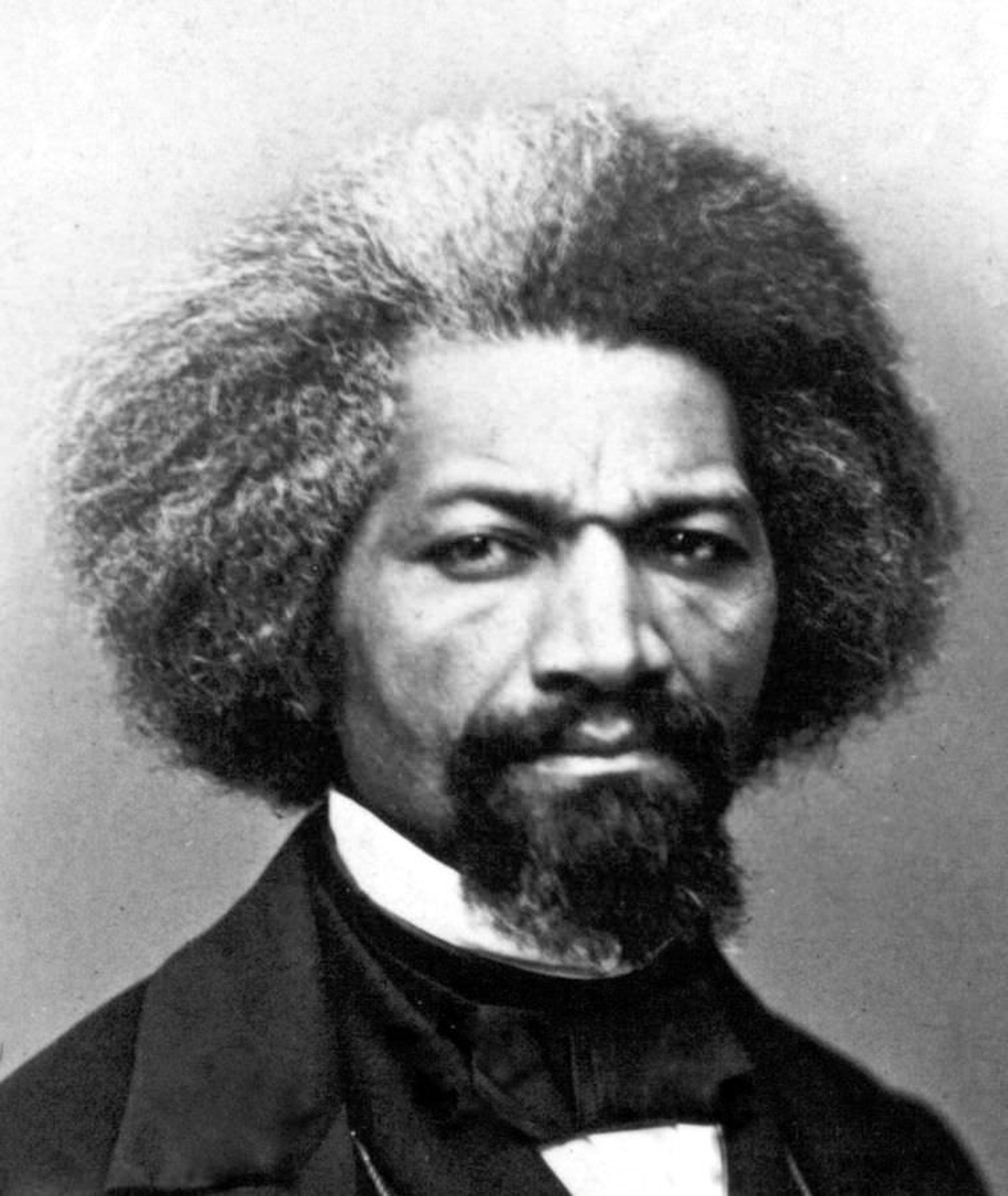

It’s worth our time to reflect on the life and words of this great man born 200 years ago this year.

Read MoreThe Stirring Elocution of Frederick Douglass →

American history abounds with great orators whose eloquence roused the people and shaped events. Names like Patrick Henry, Daniel Webster, William Lloyd Garrison, Abraham Lincoln, William Jennings Bryan, Susan B. Anthony, and Martin Luther King come to mind.

The best of them spoke with passion because their words gushed forth from wellsprings of character or experience or righteous indignation—and in the case of the great 19th-century American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, all three. He could pierce the conscience of the most stubborn foe by what he said and how he said it.

In a 1997 article for FEE, “Frederick Douglass: Heroic Orator for Liberty”, historian Jim Powell cites this description of Douglass by a first-hand observer:

He was more than six feet in height, and his majestic form, as he rose to speak, straight as an arrow, muscular, yet lithe and graceful, his flashing eye, and more than all, his voice, that rivaled Webster’s in its richness, and in the depth and sonorousness of its cadences, made up such an ideal of an orator as the listeners never forgot.

It’s worth our time to reflect on the life and words of this great man born 200 years ago this year. His story is all the more remarkable considering the circumstances of his birth and early life.

Douglass was born a slave in Maryland in 1818. He never knew who his father was and his mother died when he was seven. He spoke in later life about how hard it was on him to be forbidden to see her when she was ill, to be with her when she died, or to attend her funeral.

Slaves were rarely educated beyond the rudiments of plantation duties, it being illegal in many parts of the Old South to school them. Douglass was naturally precocious and in quiet times and places, he schooled himself—even memorizing orations of Cicero and William Pitt. Before he was 20, he was educating other blacks in his own underground classes.

As a slave, Douglass endured endless hardships and witnessed the separation of families, arbitrary punishments, and unspeakable cruelty. During it all, he taught himself to play the classical masters like Handel on the violin and nurtured a burning desire to free himself from bondage. In 1838, he managed a risky escape to freedom in the North. A few months later, upon hearing a speech by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass committed himself to bringing freedom to others suffering in slavery. His weapon of choice would not be gun, sword, or cannon, but the spoken and written word.

He went on to be America’s most recognized and celebrated black man in the five decades before his death in 1895. He advised presidents and foreign dignitaries and authored no fewer than three autobiographies. His name and image adorn buildings, streets, organizations, plays, films, and schools all over the country to this day.

Let’s take a closer look at a small portion of the eloquence of Douglass. Note the clarity of his message and the imagery of his phrases. Imagine how powerful his appeal to moral conscience must have been to those who heard this former slave in person!

At the age of 29 in 1847, he delivered an address in Syracuse, New York, titled “Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country” in which he outlined a central point of many speeches to come:

There is no conceivable reason why all colored people should not be treated according to the merits of each individual. It is not only the plain duty, but also the interest of us all, to have every colored man take the place for which he is best fitted by education, character, ability, manners, and culture. If others insist on keeping him in any lower and poorer place, it is not only his injury, but our universal loss. Yet which of our white congregations would take a colored pastor? How many of our New England villages would like to have colored postmasters, or doctors, or lawyers, or teachers in the public schools? A very slight difference in complexion suffices to keep a young man from getting a place as policeman, or fireman, or conductor, even on the horse cars. The trades-unions are closed against him, and so are many of our stores; while those which admit him are obliged to refuse him promotion on account of the unwillingness of white men to serve under him.

Later in the same speech, Douglass declared that his campaign for freedom was motivated by the highest form of patriotism: “So long as my voice can be heard on this or the other side of the Atlantic, I will hold up America to the lightning scorn of moral indignation,” he pronounced. “In doing this, I shall feel myself discharging the duty of a true patriot; for he is a lover of his country who rebukes and does not excuse its sins. It is righteousness that exalteth a nation while sin is a reproach to any people.”

Slavery, of course, was his prime target, and he could express its inherent evil better than just about anybody. You can see that in this excerpt from a lecture in 1850:

I have shown that slavery is wicked—wicked, in that it violates the great law of liberty, written on every human heart—wicked, in that it violates the first command of the Decalogue—wicked, in that it fosters the most disgusting licentiousness—wicked, in that it mars and defaces the image of God by cruel and barbarous inflictions—wicked, in that it contravenes the laws of eternal justice, and tramples in the dust all the humane and heavenly precepts of the New Testament.

To bring an end to the scourge, Douglass would collaborate with any man or woman, black or white, North or South, free or not. “I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong,” he once said when asked why he was cooperating with former slave owners. Freedom, he believed, was God-ordained for people of all colors. However, it requires hard work and determination to realize it and defend it: “A man’s rights rest in three boxes: The ballot box, the jury box and the cartridge box.”

This was a man who could speak with conviction about the importance of character because he possessed it in abundance himself. He understood that slavery was a blot on the character of the country, evidence that a moral renaissance was required. “The life of the nation is secure only while the nation is honest, truthful, and virtuous,” he said. Slavery was an equal opportunity curse because it would sooner or later come back to bite even those who seemed to benefit from it: “No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.”

Douglass was at his best when he implored others to get involved. Regarding noble causes, silence and complacency wouldn’t cut it. Good people must agitate! Reform would never come without agitation. As he put it in 1857,

The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to, and you have found out the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

Harriet Tubman, the most renowned conductor of the “Underground Railroad,” escorted nearly a hundred slaves north to freedom at great risk to herself. She was a friend to Frederick Douglass, who paid her his highest compliments in an 1868 letter:

Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day—you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt “God bless you” has been your only reward. The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism… Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you. It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony to your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come, that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

It should come as no surprise to learn that Frederick Douglass played a pivotal role in the transformation of the American conscience. For centuries before 1800, slavery was common in the world and widely accepted. A hundred years later, it was mostly gone and everywhere condemned. Among those in America who helped accomplish that noble objective, Frederick Douglass used words as weapons to amazing and lasting effect.

That a self-taught, former slave would be so central to that achievement is one of the most remarkable ironies of our history.